Bill Summary

The VALOR Act of 2025 is a comprehensive framework to pressure Venezuela’s Maduro regime and any nondemocratic successor while laying out a pathway and support package for a democratic transition. It combines policy statements, multilateral diplomacy, targeted and systemic sanctions, transparency requirements, and a prospective assistance plan to be activated once the United States determines a democratically elected government is in power.

Title I defines, in unusually specific terms, what constitutes a “democratically elected government” in Venezuela for purposes of U.S. policy resets. That determination hinges on free and fair elections with international observers; open candidate access; media access; an independent judiciary; respect for human rights and civil liberties; freedom of association and press; respect for private property; and a suite of corrective actions. Those include restoring the National Assembly’s full powers and immunities; ending interference with political parties and candidates; releasing political prisoners and allowing prison investigations; dissolving the Colectivos and any security/intelligence units credibly accused of gross human rights violations; cooperating on extradition of individuals wanted by the U.S. Department of Justice; permitting international human rights monitors; ceasing any support to violent overthrow of other governments; and freeing hostages and wrongfully detained U.S. nationals. Crucially, any transition government cannot include Nicolás Maduro or persons sanctioned by OFAC or sought by DOJ.

Title II sets the U.S. posture in multilateral bodies. The Treasury is directed to oppose seating representatives of Maduro or any nondemocratic successor at international financial institutions (IFIs) like the IMF, World Bank, and IDB. After a democratic determination, the U.S. should support seating a new government while opposing IFI assistance that does not build a stable democratic foundation. In the OAS, the U.S. must oppose measures that allow a nondemocratic Venezuelan government to participate until democracy is recognized. The bill authorizes U.S. support for independent NGOs and democracy-building efforts, urges creation of an OAS emergency fund for human rights and election observation (with at least $5 million in U.S. voluntary contributions), and promotes deployment of OAS and Inter-American Commission on Human Rights monitors. Humanitarian and civil society assistance is explicitly permitted under OFAC General License 29, subject to safeguards to prevent material benefit to the regime.

Pros

- Strong emphasis on human rights and democratic norms: The bill ties sanctions relief to concrete benchmarks like free elections, independent judiciary, media freedom, and the release of political prisoners, aligning with values-centered foreign policy.

- Multilateralism is foregrounded: It leverages the OAS and IFIs, seeking international monitors and coordinated assistance, reducing the likelihood of unilateral U.S. overreach and enhancing legitimacy.

- Humanitarian safeguards are explicit: Assistance via NGOs is authorized under OFAC General License 29 with required safeguards to avoid regime benefit, balancing pressure with concern for ordinary Venezuelans.

- Transparency and accountability: Regular reports on OFAC specific licenses and estimates of funds accessed by the regime provide oversight of sanctions policy and guard against quiet loosening that benefits autocrats.

- Clear off-ramp for sanctions: A pathway to easing pressure once democratic progress is verified can incentivize reform and avoid indefinite punitive measures that can harm civilians.

- No requirement to impose import bans: The import exception reduces risk of unintended harm to U.S. consumers and workers and avoids sudden shocks to supply chains (e.g., energy).

- Focus on civil society: Funding for democracy-building and human rights observers strengthens independent actors, not just state institutions, which is key to sustainable democratization.

- Avoids military options: It uses diplomatic and economic tools, consistent with a preference for non-kinetic approaches to democracy promotion.

- Tough, comprehensive pressure on Maduro: The act codifies and expands sanctions on PDVSA, regime debt/equity, and government property, closing loopholes (including crypto) and signaling resolve.

- Conditionality is ironclad: Sanctions remain until a verified democratic government is in place, with detailed benchmarks that exclude Maduro and other sanctioned or indicted individuals from any new government.

- Targets malign foreign influence: The policy explicitly calls out Cuba, Iran, Russia, and China, and authorizes measures against countries that materially assist the regime, aligning with broader strategic competition priorities.

- Oversight of sanctions relief: The recurring reporting and the joint resolution of disapproval give Congress a tool to prevent premature or politically motivated sanctions rollbacks.

- Protects U.S. economic interests: The explicit import exception avoids accidental mandates to ban imports that could raise costs for U.S. consumers or harm industries, preserving executive flexibility outside this statute.

- Transparency on OFAC licensing: Regular disclosure of licenses and regime-accessed funds increases accountability and curbs backdoor concessions that undercut pressure campaigns.

- Law-and-order focus: Requirements to dissolve Colectivos, extradite DOJ fugitives, and free U.S. hostages underscore a security-first posture against criminality and hostage diplomacy.

- Clear support for democratic forces: Backing for NGOs, OAS monitors, and election observation bolsters legitimate opposition and societal resilience without funding the regime.

Cons

- Risk of exacerbating humanitarian suffering: Broad financial, debt, and property-blocking measures can further constrict the economy, potentially worsening conditions for civilians despite humanitarian carve-outs.

- Secondary sanctions on countries assisting the regime may complicate diplomacy with nations like Mexico, Brazil, or global powers and could be seen as extraterritorial overreach that undermines coalition-building.

- IFIs posture could delay stabilization: Opposing some forms of IFI assistance—even under a future democratic government—if not aligned with U.S. assessments might slow urgent macroeconomic stabilization.

- Rigid criteria and exclusion clauses (e.g., barring any figure sanctioned by OFAC) may reduce flexibility for transitional negotiations where amnesties or power-sharing deals can sometimes be pragmatically necessary.

- Congressional disapproval mechanism for sanctions termination may constrain the executive’s ability to sequence confidence-building steps and could politicize the timing of relief during a fragile transition.

- Crypto and blanket property blocks may have compliance spillovers, deterring legitimate humanitarian and private sector activity out of caution, and creating de-risking that isolates Venezuelans further.

- Funding uncertainty: The assistance plan is contingent on future appropriations, potentially raising expectations without guaranteed resources, and OAS funding of $5 million is modest relative to needs.

- No mandatory import sanctions: By barring use of this act to impose import bans, the bill limits tools that some hawks might want available, including the option to block Venezuelan crude or other goods via statute.

- Relies heavily on multilateral bodies: Some conservatives are skeptical of the OAS/IFIs and may view the $5 million OAS fund and deference to IFI processes as slow, inefficient, or subject to politicization.

- Humanitarian and NGO carve-outs can leak: Even with safeguards, assistance can be diverted by the regime or used to relieve pressure on its patronage networks, potentially dulling sanctions’ bite.

- Waiver authority remains: The national security waiver for foreign persons (with only 10 days’ notice) could be seen as a loophole future administrations might use to dilute pressure for geopolitical trade-offs.

- Does not mandate broader secondary energy sanctions: It encourages partner restrictions but stops short of compulsory secondary sanctions on entities buying Venezuelan oil, which some in the GOP favor to cut regime revenue.

- Termination process might still allow an administration to sequence relief too quickly: Despite congressional review, the President controls the democratic determination and initial steps to unwind sanctions, which could be used to justify early concessions.

- Compliance burdens for U.S. businesses: Expanded blocks on debt, equity, collateral, and crypto increase due diligence costs and legal exposure for U.S. firms, even those trying to engage in humanitarian or post-transition preparation.

This bill was introduced on January 08, 2025 in the Senate.

View on Congress.gov:

https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/senate-bill/37

-

Jan 08, 2025

Read twice and referred to the Committee on Foreign Relations.

-

Jan 08, 2025

Introduced in Senate

10000

This bill has not yet been enacted into law.

No related bills found for this legislation.

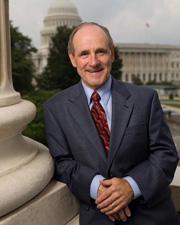

Sponsors

Policy Area: International Affairs

Associated Legislative Subjects

- Administrative law and regulatory procedures

- Business investment and capital

- Civil actions and liability

- Congressional oversight

- Currency

- Department of the Treasury

- Digital media

- Food assistance and relief

- Foreign aid and international relief

- Foreign and international banking

- Foreign loans and debt

- Foreign property

- Human rights

- International organizations and cooperation

- Latin America

- Licensing and registrations

- Multilateral development programs

- Sanctions

- Securities